CISO DRG Vol 1: Chapter 7 – Risk Management and Cyber Liability Insurance

Introduction

In this chapter, we will talk about the one fundamental issue that drives most CISOs and influences how they create and manage their security programs. That issue is risk. Our authors will note that there are numerous types of risk facing an organization from both an internal and external perspective. They will also discuss the various components of risk and the impact on an organization when risk is not managed correctly. The discussions that follow will highlight our authors’ unique viewpoints on risk in its different forms and how to accomplish risk management through security controls and new tools such as a cyber liability insurance policy.

Our authors collectively believe risk is one of the primary drivers that influences an organization and its ability to be successful. Because of risk’s enterprise-wide impact, our authors believe the modern CISO must understand their organization’s industry, regulatory requirements, and strategic initiatives. This business context will provide critical insight for CISOs as they use their security program, policies, tools, and cyber insurance to protect their organization and reduce its risk exposure to an acceptable level.

Bill highlights the four fundamental approaches that organizations will use to manage their risk. He provides a thorough analysis of how the risk management function within the organization has changed due to many of the dynamic threats now facing enterprise business environments. He describes the multitude of ways that risk can impact an organization, and from his in-depth experience provides several options that organizations can use to mitigate risk and its impact on their business operations.

Matt approaches the discussion of risk through the lens of cyber liability insurance. He breaks down how to view the management of risk through tools like an insurance policy and how to leverage this new capability for the organization. In his discussion, Matt emphasizes that for the CISO to consider using cyber insurance, they must have an understanding of the current risks facing the business, the present risk management controls in place, and the resultant gaps to address. He believes that with this knowledge a CISO is in a better position to help their organization reduce its risk exposure by implementing an appropriate cyber insurance policy.

Gary begins his discussion on risk with the pragmatic viewpoint that for CISOs to be productive in mitigating the risks facing their organization they first must establish a risk baseline. The CISO must understand what is critical to the organization and must have executive management support to prioritize cyber risk correctly. Gary delivers a thorough treatment of cyber insurance and its numerous components and provides recommendations on how to use cyber liability insurance as a tool to protect the organization.

Some of the questions the authors used to frame their thoughts for this chapter include:

♦ How to I assess my organization’s current cybersecurity status? What do I need to protect first?

♦ What must my executive team do to prioritize cybersecurity in the organization? As CISO, what components and policies must be part of my cybersecurity program to effectively manage risk and keep my executive team informed?

♦ Should my organization consider cyber insurance to reduce its risk exposure? What do policies cover and not cover? What types of coverage should my organization consider (first party/third party)?

Cybersecurity, Risk Management and Cyber Insurance – Hayslip

Across our planet, the Internet is making inroads into every society as technology moves forward exponentially. With this increase in connectivity, we see new business platforms and societies reaping the benefits of access to new business opportunities and services.

However, there is a dimmer view of this fantastic growth in technology. With every tool used for one’s benefit, there is always the dark side of how it can be used to one’s detriment. This drama of how criminals use technology against organizations highlights the unique position of the CISO.

An organization’s CISO is the subject matter expert on the dilemma of this dark side. It is considered essential that the CISO understands the organization’s risk exposure to cybercrime, compliance and regulatory issues, and new evolving threats. To do this effectively, the CISO must establish an executive-sponsored cybersecurity program, create relationships within their organization’s internal and external stakeholder communities, and continuously evaluate their organization for risk and take immediate steps to protect it from harm.

You Want Me to Protect What?

As we begin our first discussion, it is incumbent on me to remind you that the CISO is the focal point for an organization’s effort to deploy cybersecurity as a service (CaaS) and reduce the company’s risk exposure to its current technology portfolio. As previously mentioned, one of the first steps a CISO will take is to establish an executive-sponsored cybersecurity program.

This program will be the platform that a CISO can employ to gain a better understanding of the organization’s exposure to technological risk and create a mitigation plan for how to address it based on the organization’s business requirements. As it matures, this security program will also provide a foundation for the CISO to pivot from and use new workflows, security controls and technologies to enable the business to understand its risks and its partners’ risks and reduce them where appropriate.

To begin our first discussion, we will talk about cybersecurity and the inherent risk it manages for the business. We will also discuss how the CISO gains visibility into the corporate enterprise environment and how to use this knowledge for the betterment of the cybersecurity program and the company’s strategic business plans. So let’s discuss how you, as CISO, will approach this first question and how you should proceed to look for viable answers. “How do I assess my organization’s current cybersecurity status? What do I need to protect first?”

To begin our discussion, let’s first understand what type of risk we are concerned about as a CISO. In our position, we must realize “inherent cybersecurity risk,” which is the risk posed by an organization’s business activities and its connections to partners, as well as any risk-mitigating controls that are currently in place. An organization’s cybersecurity risk incorporates the type, volume, and complexity of its cyber operational components. These are the types of connections used by the applications and technology required by the organization to conduct its business operations.

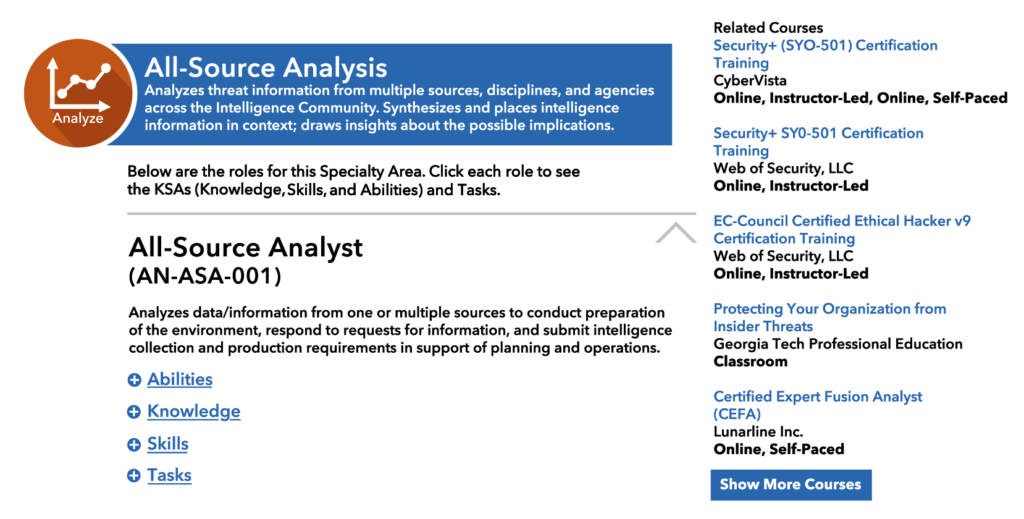

Figure 7.1 COSO Enterprise Risk Management Framework

To understand this risk, we must approach the business departments within the organization and gain insight into how they do work. We must understand the applications, data, workflows, and technologies that are required by their personnel and any projects they wish to initiate to improve their capabilities. To collect this information quickly and effectively, I would suggest you begin with an enterprise risk assessment. I have completed several of these in the past and would recommend using a framework like the NIST Risk Management Framework or the COSO Enterprise Risk Management Framework. These frameworks will provide you with a solid foundation to begin your discussion about risk within your enterprise.

As you begin your assessment, there will be components that will require you to interact with your various business departments directly. Use this assessment as an opportunity to start building the relationships you will need as a CISO. Your stakeholders have critical knowledge about your organization, and you will need them to help your program mature and grow a cyberculture within these departments.

As you work with these stakeholders, you should seek to gain the insight that you will need as a CISO, which is to understand what assets you must protect for the organization to be successful.

Questions for the CISO to Gain Insight to Critical Assets

♦ Do I understand which applications and services are critical for my organization?

♦ Do I know what data these critical applications create and where this data is stored and backed up?

♦ Does my organization have formal agreements with its critical partners that allow us visibility into how they are managing their technology-based risks??

♦ Does my executive leadershipteam understand what threats and vulnerabilities are being used by our adversaries to target the products the company presently has it its technology portfolio?

As you begin discussions with your stakeholders, there is one crucial point I want you as CISO to pay attention to and document. This critical point is the tone that you and your teams get from these stakeholders on anything associated with your cybersecurity program. Most boards of directors only speak about cybersecurity when there is a breach. If the board is routinely addressing security and senior executive management is sponsoring your security program, you should see the beginnings of cybersecurity awareness taking root in the organization’s culture.

However, if this is not the case, it will be harder for you to get accurate information when conducting your assessment. I bring this point up because it will give you much-needed insight into how you should address your stakeholders and the responses you might receive from them.

As a CISO, I have found in the past that there will be departments that will want to work with me as a partner and departments that will try to ignore me. Those that were partners I treated as equals in the process, and I championed their projects at tech review. I also included their inputs in new security policies and work processes and requested their assistance with my reluctant departments to eventually grow the trust required to conduct a full cyber risk assessment with all departments.

So back to our cyber risk assessment. As CISO you should also review current practices and overall company preparedness. Several critical processes that should be a focus of the risk assessment are:

- “Risk Management and Governance” – this component is about strong governance with clearly-defined roles and responsibilities. There should be assigned accountability to adequately identify, assess, and manage risks across the organization. How well does management account for cyber risk when implementing new technologies? Is there a formal process to review and mitigate issues as required? It is also in this process that we look at our personnel, who are the company’s first line of defense. It is here that we address whether the organization is providing cyber awareness trainingto employees and whether this training is effective in providing employees with an awareness of ongoing cyber risk.

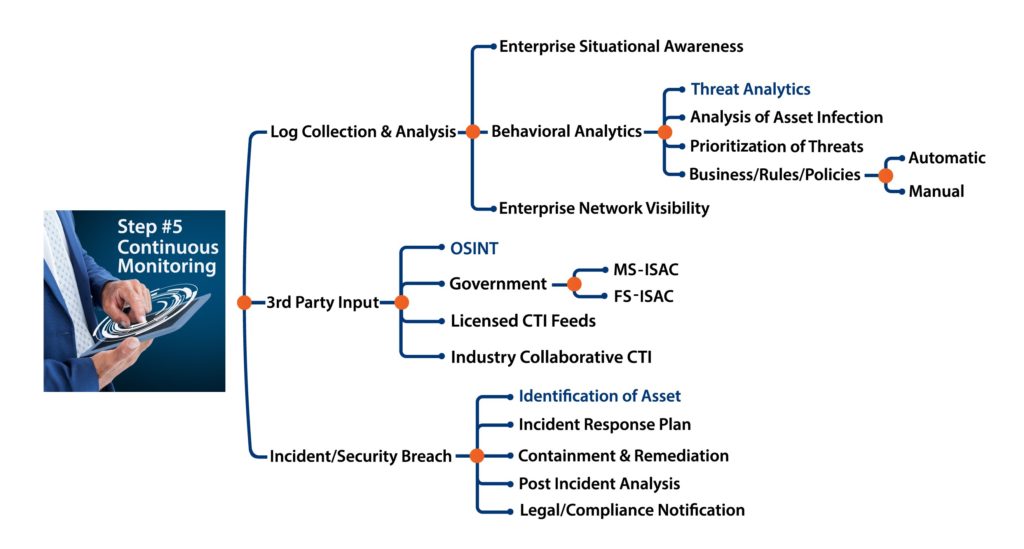

- “Threat Intelligence and Collaboration” – this component is about the processes the business has in place to collect and analyze information to identify, track and predict the intentions and activities of your adversaries. This information can be used to enhance your decision-making capabilities, providing needed visibility into the risks associated with large strategic projects. Participation in information-sharing forums such as CERT, NIST, InfraGard, MS-ISACor FS-ISAC is considered critical to the CISO. A vital element of the CISO’s job is assisting with organizational risk management and the information from these partners is instrumental in the CISO’s ability to identify, respond to, and mitigate cyber threats/incidents.

- “Security Controls” – this component focuses on the employment of security methodologies that can be preventive, detective, and corrective. Most organizations will use preventive controls, controls that are focused on preventing unauthorized access to enterprise assets. However, a mature cybersecurity program will employ multiple control types, interwoven to provide more resilient coverage against the changing cyber threat landscape. The types of controls that can be deployed to work together are:

- Preventive Controls– processes such as patch management and encryption of data in transit or at rest. These controls need to be periodically reviewed and updated as the organization’s technology portfolio

- Detective Controls– tools that are used to scan for vulnerabilities or anomalous behavior. Some of these controls are anti-virus/anti-malware solutions or new endpoint solutions.

- Corrective Controls– these are controls designed to fix issues. Examples are organizational policies such as change management, patch management, and third-party vendor management.

With the deployment of these controls don’t forget to ask yourself “what are the processes for implementing them?” Are these security control processes documented and are they periodically reviewed? What are the procedures to mitigate risk identified by these processes? As you can see, controls are like children. They will need to be fed, monitored, cared for and, as they mature, updated to ensure they effectively provide value to the organization.

- “External Third-Party Management” – this component is about the management of connectivity to the business’ third party providers, partners, customers, and others. What processes/policies should the company have in place to manage these relationships? Part of this component will be organizational directives that document company policy for executing contracts with third-party entities. Does current contract policy spell out what types of connections you require to corporate networks? Does current contract policy spell out what data will be required and document who will access it? Does current contract policy include as part of the contract a “verification of risk standard” concerning the external partner’s disaster recovery/incident response plans?

- “Incident Management” – this component is critical for the organization. It focuses on cyber incident detection and response, mitigation of identified risks, incident escalation/reporting procedures, and overall cyber resiliency. In the assessment process, you will need to identify whether the business has documented procedures for the notification of customers, regulators, and law enforcement concerning a breach. You will also need to verify that you periodically report metrics you collect on this component and its maturity to senior management. One last essential process to verify through this risk assessmentis “does the organization have documented Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity plans?” In answering this question be sure to verify that you test the plans, there are communication policies in place, and there is a documented process for how to include trusted third parties for effective communications.

As you can see from our discussion so far, in assessing the organization to develop a more thorough understanding of its inherent cybersecurity risk, you will generate an inordinate amount of data. This data focuses on the essential technology and business process components required by the organization to execute its strategic business plans. This information will be extensive and can be overwhelming, especially if the organization has numerous business verticals and international business channels. However, as CISO you now have a decision to make, and that is “what do I protect first?” Not all assets are created equal, and now it is time to prioritize with your stakeholders which ones require the most protection and the focus of your cybersecurity risk management program.

As CISO, you use a process called “asset classification” to decide the level of protection dedicated to an asset. You will find that organizations tend to overprotect assets and data. In the world of technology, not all data and assets require the same level of protection. As CISO, you will want to understand what assets make up the category of “most valuable assets” as prioritized by the business stakeholders. This means that your stakeholders will assist you in prioritizing what is important to them. A good rule of thumb to help you in this process is to ask, “If these assets are stolen, compromised, misused, or destroyed, would this result in significant hardship to the organization?” If the answer is yes, then they are critical assets and will require added protection. Once you have this list, you will also need to understand their location and, most crucially, who has access to them.

I am sure by now you are wondering what baseline should be used to assist the organization in grading these assets. You know that you will be working with the business’ various departments to identify what assets are critical and you have some excellent questions to ask yourself as you review the data you collect. However, there is a methodology for determining what is essential and requires extra protection. Some steps I would recommend are as follows:

- Identify the critical assets and business processes – following the steps I listed above, work with your stakeholders to create a prioritized list of essential assets. Some examples of asset types that fall into this category are trade secrets, market research, trading algorithms, product designs, people, and R&D research.

- Determine the assets’ value to the organization – “one size fits all” doesn’t apply when you are assessing technology, work processes, and data types. I gave you some questions to measurethe criticality of the assets under scrutiny. However, there is also the topic of compliance. You will have asset types that fall under a regulatory/compliance regime, and as such, they will have laws and fines associated with them. What this means to a CISO is that once you have your prioritized list, you will still need to review it for any items that are governed by compliance and move them towards the top of the list. You will want to ensure your business has visibility on compliance-related assets when they help you set the priorities for this list.

- Determine the risk toleranceof the organization – once you have identified and ranked the organizations’ assets, you need to determine how much risk the business is willing to accept. This idea of risk tolerance focuses on how much protection the business is willing to employ provided it doesn’t interfere with its ability to conduct operations. I have found, as CISO, that there will be times where a critical asset will not receive a specific level of protection for fear of degrading a business process. This becomes a risk the organization is willing to accept, and it is one you will need to document and develop other compensating security controls or methodologies to monitor and manage. The critical part of this step is listing those assets that have degraded protection, developing compensating controls to mitigate as much risk as possible, and then documenting the residual risk for monitoring and hopefully future mitigation.

- Set appropriate levels of protection for each asset type – This last step is a recommendation for organizations with large numbers of assets. I have used this step to separate my data into asset groups prioritized in the previous steps. Now with these identified groups, you can establish a level of controls that apply to the specific asset types, and you can determine who has responsibility for the assets. With responsibility identified, you can create a matrix of management to document who is responsible for the assets, who can make decisions about whether to accept or mitigate risk, and who will assist you and your teams in remediating any security issues.

One final aspect of identifying what needs to be protected and establishing an appropriate level of security is developing training scenarios for staff to protect their assigned assets. The CISO is expected to not only understand the complexity of risks facing the organization but know how to mitigate any cyber-related incidents quickly. This is why you will want to create training scenarios. With the work previously completed in assessing the organization’s cyber risk maturity level and establishing what assets are critical, the CISO can now take these training scenarios and include them as an appendix to the organizational incident response manual. These scenarios should be used to test the organization’s response to the ongoing list of threats it faces on a daily basis and assists it in improving its business continuity.

Cybersecurity Must Be a Priority, or Is It?

The Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) completed an international survey in 2018. This survey, titled “State of Cybersecurity 2018” (ISACA 2018), had over 2,366 cybersecurity managers and security professionals respond. It confirmed that the rate of cyber incidents continues to grow at an alarming rate and the sophistication of attack methods is evolving. Two interesting statistics from this report that I found particularly daunting were that 75% of respondents reported that they expect their organizations to fall prey to a cyberattack this year, and 60% felt their security staffs were not mature enough to handle anything beyond simple cyber incidents.

I am sure you are asking, “Why is this important?” Well, the reason is that as CISO it is your job to understand the maturity of your organization concerning cybersecurity. It is also your responsibility to ensure that your organization is prioritizing the risks your security program is designed to manage and if it is not, that you have the policies and procedures in place to educate your organization’s officers and directors accordingly. This brings us to our next topic of discussion, “What must my executive team do to prioritize cybersecurity in the organization? As CISO, what components and policies must be part of my cybersecurity program to manage risk and keep my executive team informed effectively?”

Corporate laws in every state of the United States impose fiduciary obligations on all officers and directors of companies. To fulfill these obligations, the senior management and board of directors must assume an active role in the governance, management and corporate culture of their respective organizations. In fulfilling these obligations, they must address issues that would put their business at risk. One of the greatest risks they face today is how the organization responds to the threat of cybercrime.

I like to think that organizations come together under the umbrella of cybersecurity, with the board of directors leading the effort, combined with multiple organizational components, including business units, HR, Compliance, finance, internal audit, and procurement. Through collaboration with the CISO and his or her team they can effectively execute the organization’s cybersecurity strategy – cybersecurity does not flourish in a vacuum. For this collaboration to happen, it must start at the top with the executive team. This team must demonstrate, through its actions, that cybersecurity is a priority for the business. Some specific actions that a CISO should observe from their board of directors and executive leadership teams that indicate that cybersecurity is a strategic priority are as follows (Foley & Lardner LLP. 2015):

♦ Members of the executive staff are educating themselves on the risk to the organization from cybercrime.

♦ Leadership is reviewing the status of the corporate cybersecurity program and requesting periodic updates of its maturity level and the status of any outstanding issues.

♦ The executive staff is reviewing current security plans and standing policies.

♦ Leadership is prioritizing cybersecurity projects.

♦ The board of directors and executive leadershipare requesting briefings on incident response and disaster recovery policies and any testing results. They are especially asking for information on how the organization will manage a breach and if this policy has been tested recently.

♦ Executive leadership and the organization are aware of the risk from current third-party relationships and procedures have been put in place to document and mitigate this risk to the organization.

♦ Policies are in place for the business to document and manage technology risks associated with all new third-party relationship decisions.

As the above steps demonstrate, the CISO and his/her team will be involved in assisting company leadership in addressing and reducing the risk of cybercrime. However, even with these steps, we need to remember that every organization that uses technology and employs risk reduction controls is still exposed to cybersecurity threats. Because of this evolving exposure, it is essential that corporate cybersecurity and risk management programs be integrated into the strategic operations of the company to minimize any disruptions concerning cyber incidents. For this type of well-managed program to exist, executive leadership will need to be actively involved, and the CISO will need to work with his/her leadership teams to effectively demonstrate a “standard of reasonableness,” or as it is known in the legal profession a “standard of care.”

What this means to the CISO and the executive team is a legal determination that the organization is conducting a cybersecurity risk reduction program with applicable standards of care and best practices to reduce its risk exposure. This determination is important because we know as cybersecurity professionals that breaches will occur; however, with an engaged executive team and a mature cybersecurity program, we can demonstrate that the organization is taking all reasonable steps to protect itself and the interests of its stakeholders.

Understand that in the triage of a breach cleanup many of the organization’s steps to prioritize cybersecurity will be evaluated to determine if the organization committed appropriate financial, technical, and human resources to the cybersecurity and risk management programs. The answers to these questions are critical. They could either lead to proper payments from the organization’s cyber insurance policies or the opposite, lawsuits from partners and customers who seek to recover from losses generated by the resultant cyber incident.

Recent Comments