Introduction

We begin Volume 2 with a discussion about people. As you strive to create a world-class cybersecurity program, you must recognize and address the critical human element. We look at the human element from several different perspectives. We include the technical skills that are required and how to assess them; motivating, inspiring and nurturing the people on your team; and understanding the environmental factors that impact your talent pool and your hiring decisions.

Bill Bonney offers a lot of practical advice on assessing, recruiting, motivating and developing the people on the CISO’s team. But he also recommends an honest assessment of the tasks that can realistically be outsourced to third parties and proposes that you look at how technology, specifically artificial intelligence, can help you be more effective in meeting your goals. Bill includes a bit of a call to arms for our industry to address the shortfall of qualified candidates.

Matt Stamper suggests that CISOs should carefully consider how they define each position. It is essential that requirements and job descriptions are realistic and appeal to the people you are trying to attract. Matt also thoughtfully unpacks several factors, both internal and external to the organization, which impact the composition of the talent pool for any particular hire.

Gary Hayslip takes a data-driven approach to workforce planning that acknowledges the fierce competition for talent in the field of cybersecurity and offers practical advice for motivating the people on your team. He continues using data to define a set of metrics to help the CISO determine if the talent on the team is delivering the outcomes that are needed and to help develop the training necessary to close any gaps.

Some of the questions the authors used to frame their thoughts for this chapter include:

♦ How do CISOs develop their hiring priorities to support the organization and their cybersecurity program effectively?

♦ What hard and soft skills does the CISO believe their cybersecurity program requires?

♦ How can I construct a training program that will keep my team’s knowledge, skills, and techniques current?

♦ What metrics can I use to measure the effectiveness of my cybersecurity team’s capabilities to provide security services and reduce risk to the organization?

Talent, Skills and Training – Bonney

I think it’s important to put the topics of recruiting, skills, training, and development in the larger context of talent management and the still larger context of the changing workforce demographics and the technical skills shortage that we face in industry – the so-called “War for Talent.” My point is not to give the reader comfort that this is a problem faced by many companies across most industrial sectors and throughout the entire world economy because that doesn’t absolve us from dealing with the problem, but rather, to draw attention to the true scope of the problem.

In the larger sense, we are dealing with a fundamental transformation of the use of human capital, on par with the industrial revolution. We should keep this in mind when determining how to approach our talent issues. Yes, the short-term tactical advice is always useful. But, planning for the long term can’t be ignored and will take a combination of human resource planning, government policy changes, new capacity and new approaches in our education systems, and new technology. These changes will require us to work differently with partners and suppliers to achieve the outcomes we want. We can’t rely on the old models of allocated headcount with defined duties and desired skills to just “get the work done.”

Talent and the Human Element

Let’s first put the topics for this chapter in the larger context of talent management. Talent management as a discipline traditionally includes four pillars: recruitment, learning, performance, and compensation. This chapter is focused on recruitment and learning which is done for an outcome (performance) at a price (compensation). Keep in mind that the purpose of talent management is to create a high-performing, sustainable organization that meets its strategic and operational goals and objectives. The goal we have for talent development is to:

♦ allow the Information Security team to develop the skills and capabilities to continually adapt to changing business and threat environments, thereby

♦ help the larger organization identify and manage the risks that threaten its information and operations technology, in order to

♦ safeguard the organization’s data (both generated and entrusted), and

♦ protect the people and operations from cyber and cyber-kinetic harm, thus

♦ enabling the organization to compete with less drag and friction.

I think to be successful with how we approach building and developing our team’s capabilities we need to consider the human element. Several different works that share some similarities with each other are helpful here. The first is a book called Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us (Pink 2009) by Daniel H. Pink. The second is a study conducted by Tony Schwartz of The Energy Project along with Christine Porath, an associate professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business. The study is summarized well in an article in the New York Times (Porath 2014). The third is an article in the MIT Sloan Management Review (Gunter K. Stahl 2012) called “Six Principles of Effective Global Talent Management.”

What is common to these works is the assertion that the sense of purpose that each person has for their work is more indicative of their engagement and success than their skills. The argument is that affinity is a more important predictor than efficiency.

That is not to say that skills aren’t important. On the contrary, one has little chance of being successful without possessing the skills required for the job. But it would be worth your time to review these works. Daniel Pink tells us that by providing our teams with opportunities for autonomy, mastery, and purpose, we are providing the key ingredients to motivate our people. Tony Schwartz and Christine Porath tell us that employees are vastly more satisfied and productive when four of their core needs are met:

♦ physical, through opportunities to regularly renew and recharge at work;

♦ emotional, by feeling valued and appreciated for their contributions;

♦ mental, when they can focus in an absorbed way on their most important tasks and define when and where they get their work done;

♦ and spiritual, by doing more of what they do best and enjoy most, and by feeling connected to a higher purpose at work.

Gunter Stahl, et al., found that large successful companies adhere to six key principles rather than traditional management best practices focused on maximizing the four pillars listed above. Those key principles are:

♦ alignment with strategy,

♦ internal consistency,

♦ cultural embeddedness,

♦ management involvement,

♦ a balance of global and local needs, and

♦ employer branding through differentiation.

Therefore, I’d like to suggest that we think of the people we work with, who help us achieve our outcomes, as people, not just talent. We would like to hire the best people with the right skills and mindset, help them become even better at what they do, have them share a common set of goals, and have them engaged and happy to be part of our team for the long haul.

Recruitment

With the human element considered, let’s turn to the issue of recruitment. I referred at the beginning of this chapter to the “War for Talent” and noted that we are dealing with a fundamental transformation regarding how we deploy human capital. These changes affect different industries in unique ways and the various functions within organizations in very different ways. Three factors I think we need to address are the scarcity of qualified workers, third-party service delivery, and augmentation using artificial intelligence.

Scarcity of Qualified Workers

A significant result of the industrial revolution was the migration of populations from rural to urban centers. This migration was aided by several factors. Among these factors were the ability of manufacturers to expand the capacity of their workforce, the resulting increase in productivity and profitability of doing so, the resulting elasticity of wages, and the relatively low barrier to entry (compared to both the guild system that preceded industrialization and the highly technical skillsets that are required in today’s digital workplace). While there were often labor shortages when new factories or industries popped up, the pace of industrial development, the availability of investment capital, and the speed of communications served as natural governing factors.

Still, labor shortages could at times doom businesses or at least temporarily suppress profits. In short, the demand signal was sent, and the response was the arrival of men and women ready to work. Training shifted from years of apprenticeship to mere weeks of classroom or vestibule training, but the key factor was the availability of any person ready and willing to work.

Fast-forward three hundred years, and many of the jobs we need to fill are highly specialized, requiring years of school and what amounts to years of apprenticeship. The demand signal has again been sent, and governments and universities recognize the severe shortages of highly-skilled workers, not just cybersecurity professionals. However, the pace of development in the digital age, the availability of abundant investment capital, and the instantaneous speed of communications serve as accelerators, not governors.

Enough Admiring the Problem. What Are We Going to Do About It?

First, CISOs must recognize that they are always recruiting. Even if there is no unfilled headcount today, the people you meet, the connections you forge, and the network you build will be necessary to create and maintain a pool of talented people for your organization. And while there is a minimum bar for the skills your team will need to be successful, you can only hire for so many of those skills. The cost (in hard cost and opportunity loss) of competing for and hiring fully formed senior security engineers for all positions has already become prohibitive.

Hiring the right team will be a mix of seasoned individuals from outside of the organization along with individuals you nurture. You will use your network, internal and external to your organization, to help you identify and attract both.

You could easily create a laundry list of security domains along with areas of specific process expertise from reviewing the requirements and controls listed in the eight CISSP domains, the 18 security control families from the NIST 800-53 standard, and the 12 PCI-DSS requirements. Add in various processes that have information technology and information security overlap, such as vulnerability management, change management, and mobile device management, along with security-focused activities, services and products such as threat intelligence, forensic analysis, penetration testing, intrusion detection and prevention, and the whole discipline of governance, risk and compliance, and you have a massive set of competencies from which to select job requirements.

It’s tempting to reduce this problem to simple analogies such as building a professional sports team. Drafting from the college ranks to fill skill gaps is like hiring workers early in their careers. Using free-agency can fill more senior positions. The minor leagues provide internships. And a deep bench can stand in for succession planning. These analogies can help explain the situation in simple, familiar terms, but they can also seem repetitious and shallow, and the consequences of failure are very different.

When we trivialize talent development by comparing it with building a sports team, we risk treating all professionals the same as members of sports teams – short-term combinations of skills designed to win a trophy. Failing to win a trophy is disappointing to the team and the host city, but teams can be overhauled in a matter of a few years and a trophy in 5 or 10 years, though not ideal, will still be celebrated.

The skills needed to be successful in the modern white-collar workplace (both hard and soft) are not so readily observed, as they are showcased outside of the arena of public spectacle. Employees are afforded many labor protections that professional athletes do not enjoy. And, the consequence of the team’s performance is greater than the disappointment in the execution of a billionaire’s hobby. And thus, the analogy breaks down.

The few elements of this analogy I do think can add value to our thinking are the youth leagues and skills development programs that exist across all of the major team sports. These programs are available for baseball, football, basketball, hockey, soccer, volleyball, gymnastics and even sports that are more focused on individuals, such as tennis, swimming, ice skating, skiing and golf. In fact, I can’t think of any sports that don’t have youth leagues and skills development programs, and many include community outreach, traveling ambassadors, senior leagues, and representation in K-12 physical education programs.

While not the only cause for this deep infiltration of sport at every level of our society, one major reason for this is President Kennedy’s revitalization of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. Physical fitness was seen as a critical need for all Americans to maintain a healthy lifestyle, both for their health and the cost to the nation that would most certainly result from the poor health of the population.

I do not mean to trivialize healthcare or the impact of poor health to our lives, but I do think that building a nation that is “cyber healthy” will be crucial to our citizens’ financial health and our nation’s public safety. I believe that existing programs that invest in STEM (and STEAM) education, hackathons, and other curriculum-based and after-school activities for the K-12 education system are vital to both teach skills and familiarize students and their parents, with cyber hygiene, cyber defense and where the skill and interest surfaces, cyber offense.

Investing for the Long Term

There is widespread recognition that building the skills and competencies needed to improve the overall cybersecurity of critical infrastructure requires national and coordinated attention. NIST’s National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) is focused directly on addressing this challenge. Special Publication 800-181 outlines the initiative.

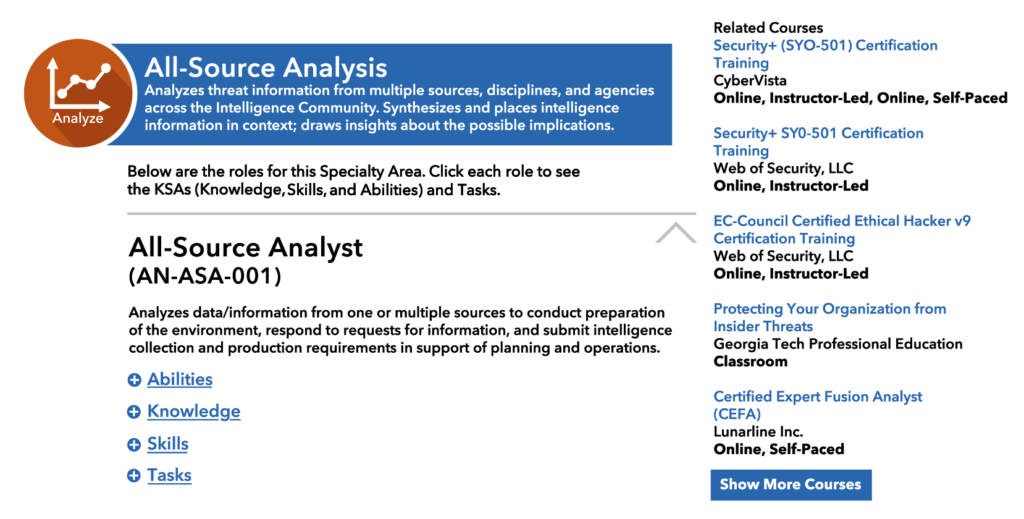

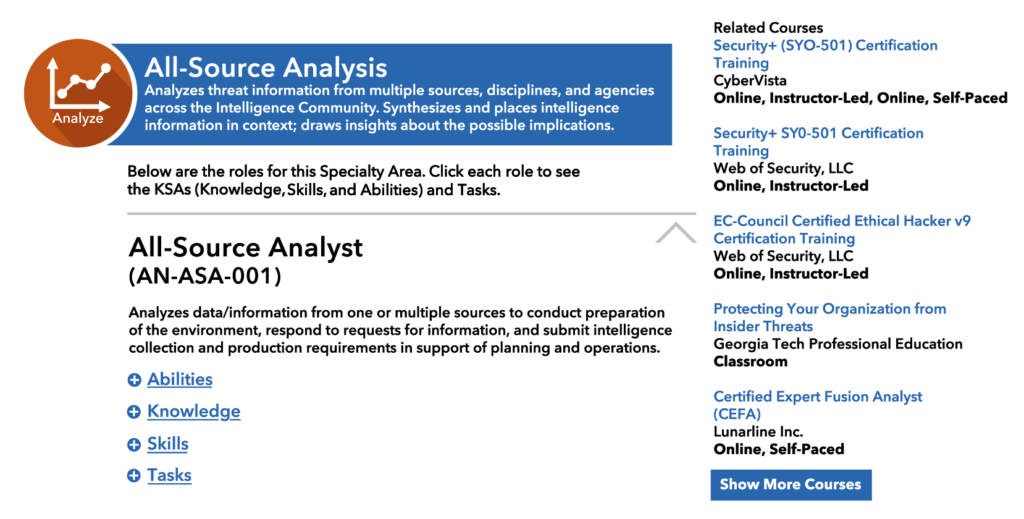

NICE offers prescriptive detail regarding seven core security functions, and 33 specialty areas of cybersecurity work. It defines 52 cybersecurity roles while providing the requisite knowledge, skills, abilities, and tasks for each role. NICE thereby helps organizations understand the types of skills and competencies that will be required to support a security program comprehensively.

In the graphics below, the seven core security functions are described, and a sample drill-down is provided. Within each core functional area, NICE provides insights and recommendations on necessary training to adequately address the function. NICE therefore provides the foundation for your cybersecurity staffing program.

Both graphics are courtesy of the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies.

Figure 10.1 The NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework

Figure 10.2 Detailed Description of Analyst Position

With the NICE skills framework, educational organizations across the nation, including K-12 schools, trade schools, community colleges, technical institutes, and universities can design programs to provide the critical training our workforce needs.

Helping the cyber workforce become productive is another gap that we must fill. The traditional model of graduating four-year degreed individuals from colleges and universities will not, by itself, overcome the worker deficit we face. On-the-job experience, in the form of internships and apprentice programs, is another vital source of learning that is necessary to allow newly trained workers to put their skills to use quickly.

Internships are excellent supplements for the typical four-year program that help the student step out of the classroom and spend critical time in the field at a variety of organizations, seeing real-world events unfold in real time. Apprenticeship programs allow a broader set of experiences that can help trainees use additional avenues to gain the skills they need. These include students who are not following the four-year degree path, workers reentering the workforce, military personnel who are transitioning into the commercial workforce, and unlocking other sources of specialists that are currently under-utilized. A critical insight is that just as the total number of seats in four-year degree programs is not adequate to provide all the cybersecurity workers we will need, and the traditional four-year program is simply not required for many of the entry-level positions that currently go unfilled.

One final recommendation about some of these novel approaches to training the cyber workforce of tomorrow is to look to cyber ranges as an option worth exploring. Cyber ranges can help you train new workers on current methods and help keep your existing workforce up-to-date. Think of cyber ranges as simulators, but under live fire. In order to train our pilot workforce without crashing real planes, we built and deployed flight simulators. Cyber-ranges scenarios are real, but with coaches and highly-skilled experts available as backup.

Hiring Who You Need

Coming back now to your immediate hiring decisions. While it’s difficult to hire individuals with a mastery of the complete list of skills and experience across each of the relevant domains, senior security engineers and security architects should have a fundamental knowledge of all of them. How can you possibly determine whether the more senior people you are hiring have the right level of broad mastery? Some rely on certifications, but I challenge how effective that is. I see a lot of value in certifications; they set an effective minimum bar in many areas, they come with an ongoing requirement for continuing education that in theory keeps people in constant learning mode, and they provide a shorthand for assessing, in aggregate, the skill level of a department.

The latter is the most perilous, though. In any population of certificate holders, just given a normal bell curve of capability, there will be some people who barely met the proficiency requirements. It is not statistically impossible to have a larger than normal collection of people on the left side of the bell. Also, the minimum bar I spoke of is just that, a minimum. It gives a reasonable assurance of familiarity with general concepts, but unfortunately, there is not enough assurance that the familiarity comes along with experiential knowledge.

So, while certifications have their purpose, we can’t solely rely on them for determining the technical fit for new hires. What other tools do we have? A lot of time and energy have gone into interviewing techniques that will both root out the hard skills (have the candidate take a coding test or configure a firewall rule) and soft skills (subject the candidate to team interviews with each team member tasked with assessing certain key soft skills such as communication skills, problem solving, managing up, and team dynamics). There are several systems out there. One of the more popular ones is the “STAR” Technique: situation, task, action, result. It’s so popular that interview candidates also use it to prepare to talk to you.

None of this is ground-breaking, and chances are good your Human Resource department will have a favorite rating system that you can adapt to the hard and soft skills that you want to test for in your screening. But most of the last two paragraphs assumes that you have a pool of reasonable candidates to start from, and your job is to screen for a fit for your team. I do happen to agree that these techniques are valuable. However, I have always found the greater challenge to be finding the reasonable pool of candidates in the first place.

That is why I said that even if there is no unfilled headcount today, the people you meet, the connections you forge, and the network you build will be necessary to create and maintain a pool of talented people for your organization. You want to make sure you always know who you would try to recruit to your organization if you should have a position open. Every interaction you have in your local security community is a recruiting event. Every meeting, every talk, every conference, every happy hour.

I’m going to put the cart before the horse to share a brief thought. The single most important recruiting tool you have is your team. If team members are motivated, work as a team, win more often than they lose, celebrate their wins, pick each other up when they are down, and care about the company they work for, others will want to come work for you too. I know that doesn’t help a lot when you are building a new team, but there is some element of that statement that you can leverage in practically any situation. They will help make your team an attractive place to be before there is a position available.

It is also important to pay attention to social tools such as LinkedIn and Twitter as well as any blogs or security forums you participate in. Make sure your profiles are up to date and that they show a positive image of you and your role. The same should be true for the people on your team. Just as companies use social tools to vet candidates, we all use social tools to vet the companies and teams we want to join. When we see a limited profile, we might believe them to be insular and two-dimensional. That may not always be accurate but underestimate the subconscious signals we pull from social tools at your own peril.

Recent Comments